“Are you sure there are no piranhas in the water,” I ask Reino Soebu, a guide from Knini Paati River Resort, as we stand atop a large boulder in the middle of the Suriname River.

I’ve already been reassured there are no crocodiles, anacondas or any of the other deadly creatures my imagination conjures up located here, but this is the South American rainforest after all and it takes me an extra pause to absorb the reality that you can actually swim here. Reino smiles and again tells me that this is a popular swimming hole with locals and that, during the nearly four decades he’s lived along the river, he’s never seen anyone attacked by any animal in such a well-cherished bathing spot.

Finally convinced, I place one foot in the semi-murky water and slowly step across the silky river bed. The brown water deepens and soon I am immersed, swimming up to lean against a ledge of rocks that hold me back from the cascade of wetness and sound that tumbles over the edge. I hang on and bob up and down in the current, looking out at the ceaseless vista of towering trees, no signs of the human world in sight. I am in the Amazon and I am completely enveloped by the wild.

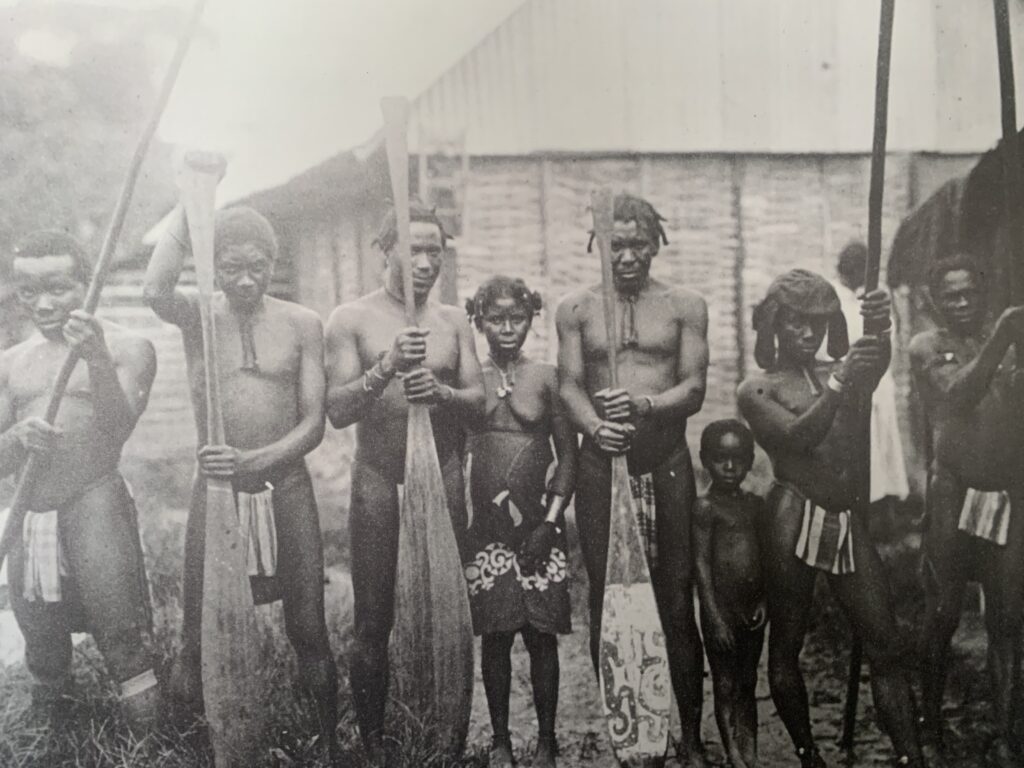

That it’s safe to swim in its namesake river only skims the surface of the unexpected experiences and history found in the Republic of Suriname. Deeper in the verdant jungle before me a more powerful revelation awaits, a story of the enduring human spirit and a triumphant legacy of freedom – South America’s smallest country is home to the world’s largest population of Maroons, the descendants of slaves who long ago escaped to freedom.

“You don’t have to go to Africa to see history from 300 years ago,” says Nelson Mae Tiapoe, owner of Knini Paati. “This history is right in America’s backyard in Suriname. Our ancestors were brave run-away slaves. For hundreds of years we’ve been free minds.”

Tiapoe belongs to the Saamaka, one of six maroon tribes that live along the river in small villages of 50-100 people. His eco-lodge is one of several in the region that offer visitors a chance to immerse themselves into an ancient culture.

Though enslaved people escaped in other parts of the Americas, the scale of Suriname’s Maroons is unmatched. According to Minority Rights Group International, around 10,000 people escaped during the two centuries slavery persisted. Throughout the centuries, the population has grown to 75,000.

Understanding how Tiapoe’s ancestors endured requires a bit of a journey through Suriname’s twisting journey to the heart of its perplexing identity. Tucked in the middle of the Guiana Highlands along the continent’s northeast coast, the territory was originally colonized by the British. It changed hands in 1667 when the Netherlands made a trade, exchanging, of all territories to their name at the time, the land that is now New York City. Dutch remains the official language though the Netherlands ceded control in 1975.

With 93% of its territory still covered in rainforest, Suriname is one of the most forested countries on the planet and one of eight to contain a portion of the Amazon. Richard Price, an anthropologist who has studied and lived in the region for more than 50 years alongside his wife Sally, says this topography was paramount for this unique culture to thrive.

“It was both the rivers and the forest that made it so difficult for colonial troops to recapture the early Saamakas and other Maroons,” said Price. “Each Saamaka clan – there are more than a dozen – took one of several routes, depending on when they escaped. The river is their means of communications, like streets and roads for us.”

The river is at the center of a visit to Knini Paati. A four-hour bus ride from the capital city of Paramaribo leads to Atjoni, a small yet bustling outpost at the mouth of the waterway that stretches nearly 300 miles south. This isn’t a place for last-minute travelers. Accommodations are few and far in between and most don’t take online bookings or credit cards. There’s also no ATM in Atjoni, only a small market and a bar that sells local Parbo beer, so travelers are advised to stock up on anything they’ll need ahead of time in Paramaribo.

It takes another hour by koorjal, a narrow, canoe-like boat with a fast motor, to reach the eco-lodge. The deft boatsman adeptly zips along and passengers gently careen side to side as the boat speeds past a swirl of green forest and slows to go over several series of non-threatening rapids. A few villages sit on the banks along the way and in each a handful of locals wave at our passing boat.

On the island of Knini Paati concrete steps lead from the dock to the raised resort. The dining room and bar are open-air, built from native brownheart and baco wood. From these common areas, a wooden walkway leads past a pool to six cabins, each flanked by a deck that provides a hammock and river view. Nature is invited in; at breakfast time monkeys chipper away in the trees and in the evening frogs bellow from the grass.

“This is a safe place where the beauty and contrasts of nature come together,” said Tipae. “My vision was to give the feeling that you really are in the jungle but you also are comfortable.”

The true gift of a stay at Knini Paati is the access it provides to observe the Saamakan way of life. The all-inclusive rate includes three meals and daily excursions, comprised of a village visit, guided rainforest hike, nocturnal wildlife tour and multiple boat rides to swimming spots.

In the village cotton blossoms on trees and cashews roast in the sun in front of thatched houses. A small group of children run along red dirt paths while their mothers wash dishes and clothes at the river’s edge. A group of men are gathered near a church; one of the villagers has died today and they are discussing funeral arrangements. The social structure here is still rooted in practices from West Africa and the tribe is ruled by a chief.

“When you visit you’re going to feel welcome,” Tipae said. “The people will talk with you. We are friendly. We Maroons go with the times, but are still keeping our traditions. We still have most things from Africa.”

That the Saamaka people endure is even more remarkable after examining their fraught path. For roughly 100 years after the first slaves escaped, the Maroons lived at war with colonists, fending off intermittent attacks. In 1762, the Maroons signed a peace treaty with the Dutch, though slavery persisted for another century. The 1980’s brought renewed conflict in the form of a civil war that led to thousands of deaths and decimated social structures.

In his book First-Time: The Historical Vision of an African American People, Price recounts this deep history and it’s impact on identity.

“Saamakas are acutely conscious of living in history, of reaping each day the fruits of their ancestors’ deeds, and of themselves possessing the potential, through their own acts, to change the shape of tomorrow’s world,” he writes.

Today threats continue to loom. A paved road from Antoji to the capitol was completed in the late 1980’s, for the first time opening direct access to Paramaribo. Young people are leaving for economic opportunities promised up north at higher rates than ever before. Foreign interests are also encroaching as mining and logging activities escalate.

On my final evening at Knini Paati I enjoy a second river swim with Reino. As the last rays of pink begin to slip out of the sky, we climb up from the river and make our way across the resort.

It’s easy to get lost in the quagmire of this complex and tragic history and each detail I’ved learned only presses me to learn more. Things seem to be changing so rapidly here and I ask him what this all means to him as a member of this community, but he advises me not to get too caught up in my quest.

“Living here you grow up with this respect for nature and sustaining traditions,” he says. “It’s not about politics, it’s not about problems, it’s about real life.”

The next day I follow Reino’s lead. I watch monkeys jump through the trees in golden sunlight. I dive under a palm leaf to shelter from a sudden burst of rain. I smile and wave at every child I meet and give out high fives when I can. I feel the cooling touch of the river on one final swim. I allow myself to be in the Amazon, completely enveloped by the wild.