A Walking Tour of African American History in Memphis

When you tell people you’re going to Memphis, one of two things happens – they either greet your statement with a blank stare, eyes glazed over by a lack of anything to say about Tennessee’s second most populous city, or they go crazy over ducks.

“You haven’t to go to the Peabody and see the ducks,” person after person gushed to me when I told them Memphis was the location of a recent business trip.

I’d already seen the ducks some years ago when I came to Memphis as a child with my family. The duck parade has been a distinguishing feature here since 1933.

I remember sitting the lobby floor of the Peabody Hotel, crown jewel of the Mississippi River and watching a group of feathered friends waddling along a red carpet to the central fountain. But as I dig into the realms of my memory and try to dig up some feeling from that moment to write about here I come up blank.

As I dig another feeling floats up – the mixture of guilt, shame and horror my ten year old self felt as I stood in front of the Lorraine Motel, the faded paint and basic exterior a jarring juxtaposition from the opulent Peabody, as my parents explained that this was where Civil Rights Leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was shot, and that his death could have been prevented had he been able to stay at a more sheltered hotel with closed hallways and better security, but during this time period Memphis was segregated, and because he was black he didn’t have that option. Here the shots could so easily get in.

This is the feeling from Memphis that I’ve carried with me into adulthood, not the joy of ducks. And while I did spend an obligatory 15-minutes of my recent stay amongst throngs of iphones at the duck parade, I used my spare time to explore a deeper topic instead.

African American History in Memphis

Before I continue to delve into the topic of African American history in Memphis, I feel the need to back up and say this – I’m aware that I am a white woman who has reaped many benefits in life due to her white privilege. I’m also aware that race is a tender topic and that I may not be the best authority to muse on such a topic.

But now is not the time for silence. Now is the time for all of us to share what we see and learn in hopes that the knowledge will be absorbed by someone else. Because passing on knowledge is essential in our pursuit of forward progress.

My ancestors willingly crossed the Atlantic in ships to come to America in the 1800’s. I know and carry their names. I can look at a map and point out the towns in Sweden in Denmark where they came from. My friend Tim’s ancestors had no choice. They came across shackled to ships in dark, cramped spaces not fit for humans. He knows no names, only that they were survivors hailing from somewhere across a large swarth of Western Africa.

It’s important, now more than ever, to acknowledge this disparity in beginnings, to educate ourselves as deeply as possible about the history of our country so that we know the truth of where we came from and use this truth to make decisions that benefit the lives of all our fellow citizens.

The wealth of attractions, museums and history and Memphis make the city an incredible base to explore the topic of African American history. The museum walking tour I mapped out tells the story of African American history in chronological order. It painted a more developed picture of this topic for me and broadened my knowledge. If you are reading and follow in my footsteps I hope it will do the same for you.

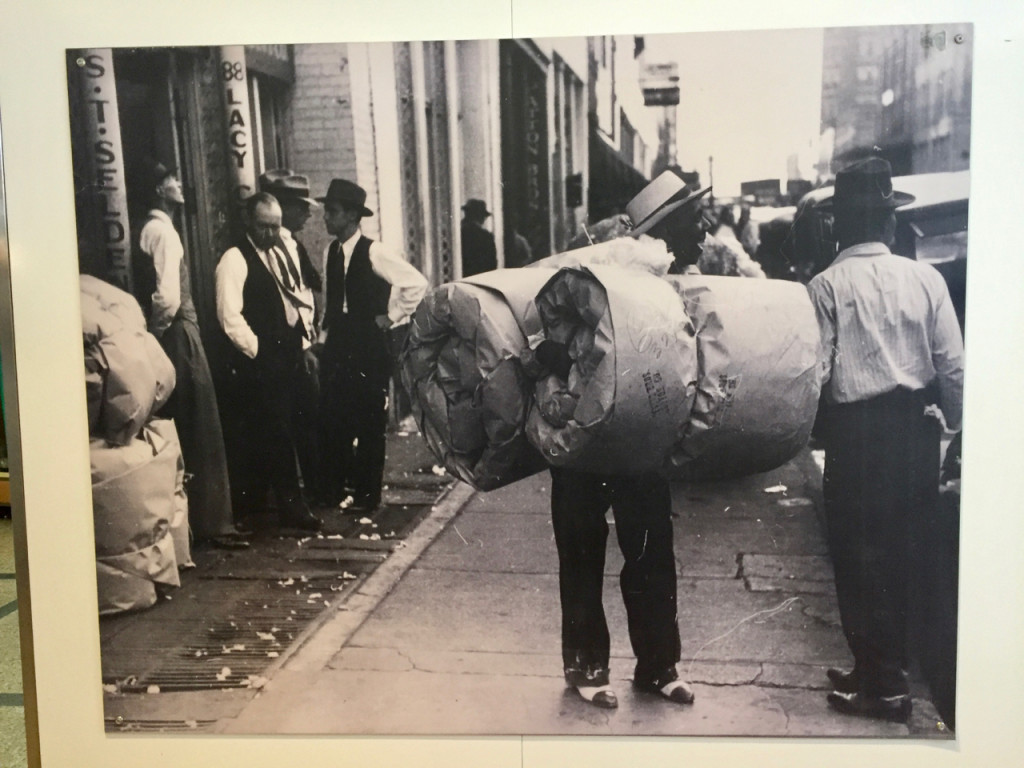

Stop #1: The Cotton Museum at the Memphis Cotton Exchange

Cotton is king. This is the lesson that forms the basis of everything I’ll discuss today.

While this crop may seem to hold little importance in our daily lives today, cotton had a deeply profound impact on our country’s history and the way our society was shaped. Cotton is the primary reason why slaves were imported from Africa to the United States in the first place.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, increasing demand for this crop from England made the value of cotton skyrocket. In fact, before the civil war, cotton exceeded the value of all other exports from the United States combined. Are you getting the idea here? Cotton was huge, and it held the potential to make people very wealthy.

The soil and irrigation from the Mississippi River made the south of the United States an ideal environment to grow cotton. And yet, cotton is a labor-intensive crop to harvest. If plantation owners were to maximize profits, they needed a cheap labor source. When the cotton gin was invented in 1793 allowing for seeds and fibers to be mechanically separated, this potential for wealth only further expanded. Thus, cotton fueled the slave trade.

Set in the Memphis Cotton Exchange in the heart of downtown, the Cotton Museum chronicles the history of cotton in the world and in the United States. The city of Memphis itself was founded in 1816 as a shipping port for cotton and a major hub in the slave trade. It’s essential to stop at the Cotton Museum first to understand the full role that cotton played in fueling the slave trade in the United States.

Stop #2: Slave Haven Underground Railroad Museum

Slavery is an uncomfortable topic. Some exhibits have a tendency to avoid these uncomfortable feelings by presenting slavery as a broad institution, thereby skirting the horrific reality of what slavery meant for the individuals who were living it.

On the contrary, the Slave Haven Underground Railroad Museum hits the heart. With guided tours through exhibits that examine the brutal uprooting of Africans ferried to America, daily life for slaves, hurtful stereotypes that continue to plague the black community today, and the workings of underground railroad and abolitionist movements, the museum presents a reflective and multifaceted examination of slavery.

Here history is broken down on a deeply personal level and visitors won’t leave without a great sense of feeling. Our tour began with an examination of symbols used in quilts to help young slaves prepare for the journey to freedom. While decoding spirituals, our guide led the entire group in singing Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, and you can bet there wasn’t a dry eye in the house.

“You can stay a slave and die a slave,” our guide says, “or you could run away.”

The museum is set in the Burkle Estate, a private home built by German immigrant Jacob Burkle in 1849. Publicly a live stock trader, Burkle built the house with the intention of using the space to help slaves escape. Visitors can get up close to the tiny crawl space, a small, damp and dark hole my 21st century body probably wouldn’t fit through, where escaping slaves would use to enter the cellar and wait until the next ship was schedule to depart, continuing their journey up the Mississippi River.

“You may be thinking, what does this have to do with me,” our guide said at the end of the tour. “Well, what if Mr. Burkle didn’t help? What if he turned the other cheek? A lot of people wouldn’t have been free. We all can help fight injustice in this world.”

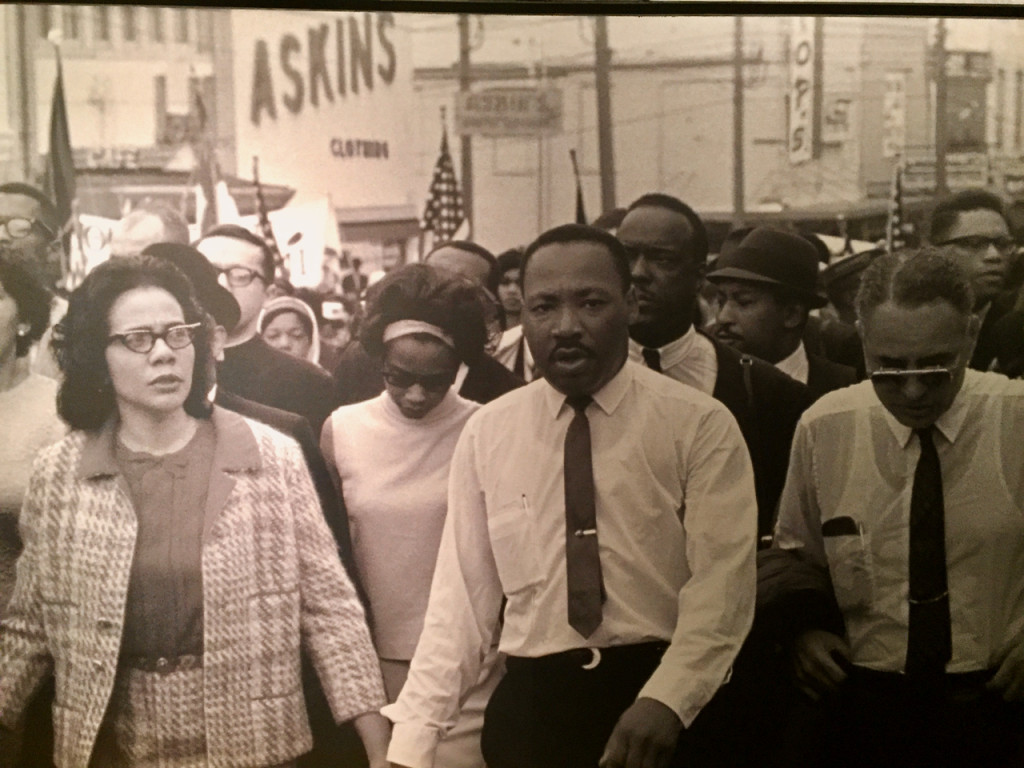

Stop #3: National Civil Rights Museum

The National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel is the most famous of all Memphis museums. It’s a fantastic museum, but it’s also very crowded. I was grateful to have the opportunity to prime my knowledge – and feel the pain of this history – in more intimate settings before seeing the very important exhibits here.

The Lorraine Motel is where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968. He was shot in room 306 while visiting the city to help organize strikes for sanitation workers. Visitors can pass by the room where MLK was shot and reflect on the last moments of this brave man’s life. The motel has been converted into an expansive museum with exhibits that document African American history from the beginning of slavery and the Civil War to Jim Crow laws and the Civil Rights movement.

The exhibits here are designed to immerse visitors into key chapters of history – from a recreation of the hull of a slave ship where visitors can get a sense of the small spaces used to transport slaves across the Atlantic to audio recordings of first-person accounts of life under Jim Crow laws to a vintage Montgomery city bus where visitors can climb aboard and hear the altercation between Rosa Parks and a public transit system worker.

I stood in front of a different bus in another exhibit that documented the Freedom Riders – nonviolent protesters who rode buses into southern cities to challenge illegal segregation in the bus system in the 1960s.

The bus in the exhibit is a replica of a bus that was firebombed in Alabama in 1961. As I stood in front of this bus a woman near me started crying.

“Oh my gosh,” she exclaimed. “ This is the bus that they burned in Alabama. I remember seeing this in the news as a little girl,” she continued, tears flowing down her face.

Tears started streaming down my face too, evoked by the pain in her voice. Her comments serve as a stark reminder that this history isn’t very distant – just more than 50 years ago the south was still segregated. The journey isn’t over yet. My do we have a long way to go.