There’s no way to prepare emotionally for a visit to Auschwitz.

This is what Pawel Sawicki from the press team tells me on a crisp morning in Poland as we walk the grounds of Nazi Germany’s largest concentration camp and unearth horrifying detail after horrifying detail of the place where 1.1 million people were murdered.

The Importance of Visiting Auschwitz

“The contact with this authentic sight is something you can’t find in a classroom,” he says. “It’s an experience that will touch something [unique]. There are so many sensitive things here and what touches that sensitive part [of the heart] is different [for every visitor].”

The string inside my heart is not cut to a breaking point as we walk under the dark, twisted iron of the ‘Arbeit macht frei’ gate, a gate which, despite its infamously symbolic status, very few of those who perished during the camp’s four and a half years of existence actually walked through. What is known today as Auschwitz was actually a collection of camps, together forming the largest concentration and death camp during the Nazi regime.

This sign that cruelly states, “work makes you free,” marks the entrance to Auschwitz I, a concentration camp constructed in 1940 for political prisoners. Beginning in 1941, Jewish prisoners, in total 90% of the victims who perished, were shipped to Auschwitz II-Birkenau, an extermination camp, where the vast majority were immediately gassed to death.

I do not cry as Pawel leads me past glass cases piled high with shoes, glasses, suitcases, pots and pans, –in total more than 80,000 artifacts put on display by survivors to show the masses of lives destroyed during the Holocaust.

The survivors were “no longer shocked by individual death, which they saw all the time,” explains Pawel. For them, “the scale was what was shocking.”

But all these torn and dusty objects still can’t help me comprehend the scale, for the mass destruction that took place at Auschwitz is unfathomable. One in six Jews who died in the Holocaust were murdered here, and more people died here than the British and American loses of World War II combined.

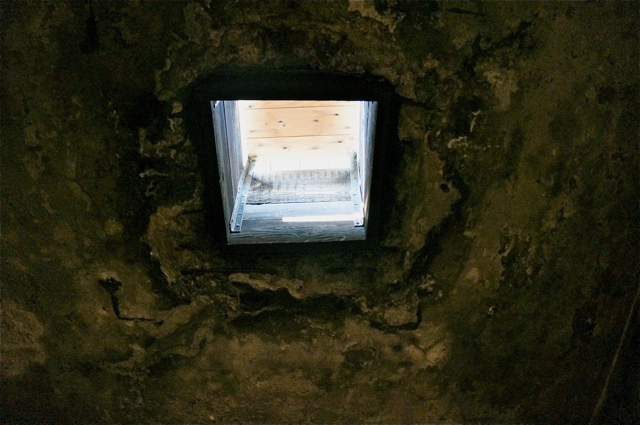

Stepping into Crematory I, the only gas chamber still standing at Auschwitz, horrifies any potential tears right back in to my body. This building still exists having been overlooked during the Nazi’s rushed attempts to destroy evidence of their actions in the final days before liberation because in 1944 it was converted to an air-raid bunker, following the completion of four much larger gas chambers at Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

The long, narrow walls are cold and coffin like. Light peeps into the dark space through holes in the roof, the very holes where the Nazis poured the poisonous Zyklon , extinguishing an unknown number of lives. Though reports of nail marks on the walls are just internet rumors, death still fills this space, and it is marked with flowers and candles, a memorial to those lost.

“These were not monsters,” Pawel says of the Nazis, rebuking this common term he feels gives the perpetrators an excuse for their actions. “These were educated people and they used all their knowledge to do this.”

At Auschwitz II- Birkenau we ascend the main guard tower, a building I’ve seen in so many films, and my string stays intact as a panoramic view unfolds.

It’s massive.

Auschwitz is massive.

I’ll say it again – this camp is huge.

Pawel reels off statistics and details of the disembarking process that occurred on the train tracks below but I’m so overwhelmed by the rows and rows and rows of bunkers and the empty space that I know was filled with people who died, I can’t take much of it in.

I stare out at the open space and I ponder how different this is than the image my sixth grade self acquired when I first learned about the Holocaust by reading Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl.

The Holocaust was not, as I had understood then, Anne Frank and her family dying. It was thousands of Anne Franks and Edith Franks and Peter van Pels, exiting trains onto the ground below, filling the space before me, and walking to their deaths, whether immediate by gassing or semi-postponed by being pulled aside to live in the camps, only to quickly succumb to disease and starvation and heartbreak.

The Holocaust was thousands of people gathered here and at other camps elsewhere to die and then the next day it happening all over again. And again. And again. And again, until the lives of 11,283,000 people were extinguished.

“Survivors, from the very beginning, wanted to keep this place intact so that it never happened again,” Pawel says. “But unfortunately humanity didn’t learn this lesson and the genocides happened and they still happen [around the world today].”

What cuts my string lies past the barracks, where Pawel’s words bring to life the wooden bunks, damp and diseased from the bodily fluids that oozed nightly down the three-tiers of cardboard-thin bodies stacked in the cramped space, spreading death.

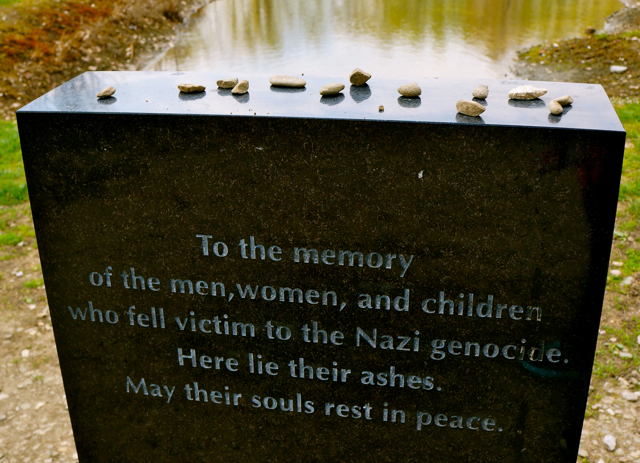

What cuts my string lies past the ruins of the gas chambers, each built to kill 2,000 people in under an hour, where prisoners spent a full day, day after day, clearing, shaving and searching the corpses for valuables before burning them to ashes.

What cuts my string lies past the International Monument, dedicated in 1967 to all those murdered under fascism, “a cry of despair and a warning to humanity,” where, on this particular sunny day, a small group of Jewish youth are gathered, heads bowed, reciting prayers in Hebrew.

What cuts my string is past all this, in a secluded corner of the massive camp, in a small brick building once known as the Central Sauna where clothes and belongings from the victims were processed, disinfected and shipped to Germany.

In a small, inconsequential room in this empty building the walls are filled with family photographs found in belongings taken from deportees directly after their arrival to Auschwitz.

One wall is covered with photos of women, and here, surrounded by all these faces and photographs that look so similar to the ones my friends and I post on Facebook, the thread of my string is swiftly and forcefully snipped. Alone in the stillness my sobs echo off the walls.

A young mother tenderly holds her awkward, chubby prepubescent daughter. I was once that daughter, rushing home to my mom after a bad day of being teased at school. Someday I hope to be that mother.

A young woman leans against a tree and flashes the most brilliant and flirtatious smile. I know she is in love with an unseen man who is taking her photograph because I was in love once and flashed him that same secret smile as he took my picture. Someday I hope to be in love again.

Another woman close to my age sits on a railing overlooking a wide panoramic view of the beach, her face filled with glee. I know she is thrilled to be exploring someplace new because this is the same smile I’ve shown in so many of the pictures taken of me on the road. Someday I hope to be able to say I’ve seen the whole world.

My sobs choke out fueled by the realization that in an hour I will walk away from this place of horror and my feet can take me wherever in the world it is I want to go and toward whatever someday dreams I wish to pursue.

But these women before me, many I’m sure more beautiful, more compassionate, more innocent, more intelligent than I am and will ever be, could not walk away. They died here.

I sit and wonder what it all means, a question of course, to which there is no answer.

“I don’t believe that anyone is able to have a full understanding [of the Holocaust], “ Pawel told me before giving me time to experience Auschwitz on my own. “The more you know, the more questions you have. And new questions and new doubts are [always] coming up.”

There is no meaning in the Holocaust, but there is great meaning in my visit today as I feel the pain of the Holocaust more deeply than I have ever felt it before.

The meaning in my visit today is simple. It means I must love as much as I can and see as much of the world as I can and be as purposeful and happy as I can because I can and these women, and the babies and the men who perished here, could not.

Of all the places I’ve been to as I’ve trekked through some 20 countries in Europe, Auschwitz is the most important place I’ve visited. I hope I don’t ever forget what I felt as I sat in that former death camp building and stared up at those women’s faces through my tears. I think everyone should go to Auschwitz and find what cuts their string. See it and feel it as deeply as you can.

Note: A special thank you to Pawel Sawicki for spending the day with me and teaching me the importance of visiting Auschwitz. Thank you Pawel for working day after day in this place of horror teaching others the facts and the stories of what happened here to the media so they may spread the message in hopes that the world will never forget.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Sara Parr

Lauren, this was an incredible piece. Thank you, as always, for putting this much care and passion into your posts so that your readers can feel so close to what you’re describing.

Lauren

Sara, thank you so much for taking the time to, not only read my work but let me know how you felt about it. I appreciate your support and am glad my words were able to move you!

Debbie Wong

Such a thoughtful post. Wow, it really made me pause for a second to think about how this could’ve happened so many years ago. And here’s the living proof of the awful side of humanity. Thanks for sharing this piece. Pictures said a lot too.

Debbie

@debbieylwong

Lauren

Debbie thank you so much for taking the time to share your thoughts on my piece with me. I too have spent many nights since my visit to Auschwitz wondering over and over how so profound destruction could have happened.

Lauren Meshkin @BonVoyageLauren

Such a beautiful but haunting post. I cried just reading this so I can’t even imagine how emotional it is actually being there. Thank you for sharing your visit and inspiring me to visit one day soon.

Angie Swann

Lauren – what an insightful post this is! I can only imagine how you felt after seeing all of the sights to then go on and see all those photographs and wonder about those women. This was a beautiful post and it makes everyone think how terrified those people must have been. I was also very interested in the Holocaust after reading about Anne Frank and I applaud you for having the courage to go and visit. Thanks for sharing!

Lauren

Thanks for reading and commenting Angie!

dad

hi lauren. your story is incredible, you really have a gift. very sad that so much hurt can happen. love you

.

Pingback: Lauren Salisbury of Something In Her Ramblings • Cooperatize Journal